Advice to Parents:

What to do when your child is abusing drugs or alcohol

(Note: “Addiction” refers to addiction to drugs or to alcohol.)

Susan Thesenga

Prologue

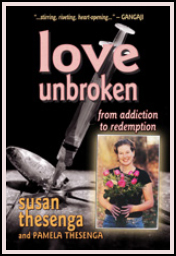

Love Unbroken is the story of my ten-year ordeal in dealing with the disease of drug addiction from which my daughter Pam suffered. During the time of her active addiction Pamela and I were both taken to the very bottom—facing insanity and the prospect of our own death, shattering our ideas about who we thought we were, and breaking our hearts wide open. And yet … passing through the destruction of what we had been brought surprising healing. Our unusual path to recovery is described in Love Unbroken.

In writing this summary I hope to pass on to other conscientious parents what I learned, so that others may benefit from my experience. To fully understand my journey as the parent of an addict, I invite you to read the book.

Advice to Parents

I was taken through various stages in my healing from the family disease of addiction. Through pursuing my own recovery I was then able to become a positive force for my daughter Pamela when she was ready to face her addiction and seek her recovery.

These steps do not depend on following any particular spiritual path; they are universal. They also do not unfold in the rational, linear form presented here for the sake of clarity.

No matter what you do, no one can promise that your child will recover from addiction. However, I can assure you that if you do everything recommended here, your life will change for the better. And then you will have a much better chance of having a positive impact on the life of your loved one suffering from addiction.

The stages of my growth were:

2.I talked with my child about her use of drugs

3. I educated myself about the family disease of addiction:

4. I educated myself about the underlying psychological and spiritual issues of my child:

5. I educated myself about drugs

6. I looked at my own co-dependency; I did my own inner work:

7. I stopped taking my daughter’s behavior personally; I detached with love:

8. I let go of unnecessary caretaking:

9. I learned to take care of myself:

10. I let go of control. I surrendered to a Higher Power:

11. I maintained a loving alliance with my daughter:

12. I was there when she was ready for treatment

And somewhere along the way: I became my own authority:

I’m first going to share with you the final step in my learning because it’s relevant before you read this advice.

I became my own authority:

While this suggestion may best be absorbed after you’ve gone through the earlier stages in dealing with drug abuse and addiction, I offer it here at the beginning so you will know not to let my advice, or anyone else’s, replace your own innate loving intelligence. I consulted many different experts in addiction but, in the end, I had to become my own authority, to trust my own heart and its deepest wisdom.

When you have a troubled child, you will get all kinds of advice from others. Some advice will be unhelpful, other advice will be helpful, but difficult to follow. Some of the best advice will challenge your instinctive parental behavior—such as always taking care of your child, always defending your child, and always trying to protect her from pain. You will have to un-learn some natural parental responses that are actually unhelpful in parenting an addicted child.

But in the end, you are still the person who knows your child best, and therefore, you are the one who can best help your child.

This may be difficult for you to believe because the family disease of addiction will erode your self-esteem, and will bring times of guilt, regret, fear and self-doubt. Sooner or later you will encounter self-blame: “Since my child is an addict, what horrible things must I have done as a parent to make him/her this way?” This thought is not true; the disease of addiction from which your child suffers was not caused by your behavior.

If you fall into believing this untrue, destructive thought, you will suffer from the “bad parent” syndrome (as I did for years). This will undermine your self-confidence and make you very susceptible to giving over to the authority of “addiction experts” and others who will tell you how to parent your child.

Instead…Learn to honor yourself. Find your inner authority. Trust your own wisdom, even as you also listen to others and learn what works and what doesn’t work in this particular parenting challenge. Don’t underestimate the positive role you can play in your child’s recovery.

A parent’s unconditional love is potentially the most powerful healing force in the life of an addict/alcoholic, so don’t be afraid to trust your own loving heart.

Here are the steps I went through:

This is crucial but very difficult. Denial is a major feature of the disease of addiction—for both addicts and their families. Getting out of denial is the necessary first step both for your healing and for developing your potential for helping your child.

As parents we are emotionally involved with our children. This is not a bad thing. Some will tell you that you aren’t objective and therefore shouldn’t try to help; don’t get shamed into inaction by that accusation. Again I believe your loving emotional connection with your child is probably the single most important thread linking your child to sanity.

However, we have to work hard not to let our emotional involvement color our perception of the reality of what is going on with our children. We often see through rose-colored glasses: we want to believe what we want to believe. We want to see him as the lovable child he once was, or as the adolescent or adult we hoped and dreamed he would become.

But, if your child is abusing drugs, then likely the drugs have hijacked the child you love and turned him into someone you barely recognize. You have to see his behavior as it is now, not as you would like it to be.

If you are uncertain about their drug use/abuse, look for the signs. If they are abusing drugs, they will likely: lie, hide, minimize or justify their drug use, try to manipulate you for favors and money, want you to bail them out of jams, have erratic hours and sleepless nights, have a roller-coaster emotional life with many interpersonal dramas, lose or be unable to get a job, or start doing poorly or failing in their school work, and likely will steal from you and others. Check out their stories by talking with their school, office, or friends.

If your child is living at home I would strongly recommend getting home drug tests and testing her regularly (but unpredictably) as a condition for living in your house. Or, if she is out of the home but receiving your financial support, give drug tests as a condition for her receiving that support. (I did this for many years.) Keep close track of your money so you can know if she is stealing. Notice her sleeping habits to see if something is amiss. Listen to (but also check out the stories of) school officials or friends or neighbors who report a problem to you. Do not automatically take your child’s “side” by believing her stories. At the same time don’t accuse her or jump to negative conclusions. Dark-colored glasses are no better than rose-colored ones for seeing the truth.

Instead put on the clear lenses of a detective seeking the facts. We have to be willing to drop the storyline in our own heads about who our children are, to drop the demand that they be who we want them to be or who we think they should be, and to see clearly what actually is happening. This is an act of love, no matter what accusations your child might make to the contrary. Of course you want to respect his privacy as much as feasible, but serious drug abuse is a life-threatening disease and, if you are going to be helpful, you have to find out what’s going on even if it means snooping in his room, and talking to people behind his back, and insisting on his being tested for drugs.

Do not defend yourself or your child against the truth: be willing to acknowledge what’s really going on. Remember that you are entitled to know what goes on in your own house or with any child to whom you give any form of financial support. Try to stay objective rather than giving in to the temptation to get hysterical with each new fact discovered. Breathe deep and repeat often, “It is as it is.”

2. I talked with my child about her use of drugs:

Once you know the truth, you can have an intelligent conversation/ confrontation/ intervention with your child. You might want to have someone else with you—the child’s other parent or another sibling, a trusted friend, or a counselor—when you have your talk. Find out if your child is still in denial, or minimizing, or justifying his drug use. Find out if he is interested in stopping or not. Find out exactly what drugs he is using and for what purpose (see section later about educating yourself about drugs).

This talk will only be useful if you stay calm and objective (remember to put on the clear lenses of the objective scientist seeking the truth). If you give in to unfounded accusations, hysteria, blame, punishing, coercion, or moralizing, you’re just adding to the drama. Stop talking and wait for another time to talk. You want, so far as possible, for your child to see you as an ally, not an enemy. This may or may not be possible (depending on the addict’s state of mind and capacity for self-responsibility), but it’s worth the effort.

When you talk to your child about her drug use, she may or may not tell you the truth. She may deny, minimize or justify her use. It doesn’t mean she is a liar or morally defective. Her addiction requires this of her because the drugs become the most important thing in her life, taking priority over everything else. She has to do whatever she can to protect her continued use. She is (usually) suffering terrible guilt about her lying, but she still can’t stop hiding because that’s just the nature of the disease.

You have to learn to trust your own inner authority—what does your gut tell you is really going on here? Can you trust your intuition without demanding that your child see it the way that you do? Can you maintain your love for him even when he is in the grips of a disease which causes him to lie, steal, and manipulate? Can you consider setting limits, boundaries and consequences without needing to punish?

Talk with your child about options. Remember that you are in charge of your own house and your own money. You don’t have to kick your child out of the house just because you have discovered he is using. But you also don’t have to continue providing shelter (if he is legally an adult) if he abuses the privilege of living with you. There are many possible options for what to do next. But first you have to know exactly what you are dealing with by assessing the situation and the addict’s state of mind, including whether or not your child needs or wants help.

If your child is underage, you still have legal control. I recommend you use your legal right to make decisions for your child. Get professional help for the family so you can set and keep limits for him at home—like setting curfews, doing drug tests, and requiring attendance at Twelve Step meetings. If he’s acting out so badly you can’t keep him home, research treatment centers or therapeutic boarding schools. If such facilities are out of reach for you financially, research what additional support can be found in your community.

If your child is over legal age, you’ll need to work with him in order for him to get into treatment, but remember that you do still have control over your own house and money; you don’t have to take care of him. If your child has serious mental/emotional issues, see if he is opent to getting help for his issues. (A good therapist will recognize that an addict cannot progress in therapy without also getting clean.) If your child is a mentally competent adult, and he has no interest in getting help for his addiction, you need to learn how to detach and let the disease take its course (see later steps).

3. I educated myself about the family disease of addiction:

If your child had cancer, you’d research everything you could about their disease—and how to treat it. Do the same with their disease of drug addiction. You may consult your family physician, but remember that doctors are not always well trained to deal with addiction; those who do not understand the nature of addiction can do more harm than good.

The very best resources are the literature of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and Al-Anon (for family and friends of addicts and alcoholics). Be sure to read what is called “The Big Book”. Go to an open (that means open to people other than the addicts themselves) AA or NA meeting and ask questions of those in recovery. They are happy to help you get clear about the nature of the disease and to share with you what worked for them to begin their recovery. An important moment in my own recovery was talking to a former heroin addict who shared that the only thing that got through to him was when his mother kicked him out of the house.

One of the important things you will learn is that relapses are part of recovery; for most addicts it takes a lot of relapses before they finally get firmly on the path of being clean and sober. My daughter had three serious, though relatively short, relapses after she finally entered on a path of sobriety. Of course each one was devastating, but, over time, I learned to not be quite so shocked by it.

Going to Al-Anon or FA (Families Anonymous) meetings is essential. This fellowship for friends and families of alcoholics and addicts is crucial for those struggling with drug abuse in the family. Get the support of fellow sufferers–usually parents or spouses—who have been where you are. Also you’ll find out that addiction is a family disease and that everyone in the family is affected by it. And you will find out that you didn’t cause, can’t control, and can’t cure the disease of your child, but you can contribute to it by enabling behaviors.

If you want to help the addict, you must first get sane yourself. Remember when you ride in an airplane the stewardess tells you to get your oxygen mask on first, before trying to put one on your child? If your child is an active addict, you really need these meetings to “get on your own oxygen mask” before you can help anyone else.

You will learn a lot there about what you can and can’t do to help your child and what you may be doing that indirectly contributes to their continuing abuse of drugs. (But also remember that you are the final authority, no one else in any meeting can tell you what is right for you or for your child).

You will learn how devastating drug addiction is. Drugs hijack the person you love. Deep inside that lovable child and promising adolescent are still there. But the drugs create a persona that is designed for one thing: to protect the continued use of drugs. It’s a Dr. Jekyll (the doctor) and Mr. Hyde (the monster he created) thing. Just as you wouldn’t trust Mr. Hyde with your money or your tenderness, you can’t trust the outward persona of the active drug addict.

You will also come to understand the effect that your child’s addiction has on the whole family. Be kind with yourself if you get hysterical (I did many times) or if you get conned. One feature of the family disease is that we all go a little crazy—with confusion, with uncertainty, with denial—not just the addict. I went through unnecessary shame and self-criticism each time I found out that I had believed my daughter’s lies and each time she relapsed and I hadn’t seen it coming. Of course we want to believe the best, and are shocked by our child’s crazy behavior. So be gentle with yourself.

4. I educated myself about the underlying psychological and spiritual issues of my child:

Most drug addicts have underlying psychological problems, usually stemming from early trauma and/or sexual abuse. Frequent diagnoses for addicts include: dissociative disorder, attachment disorder, borderline personality disorder, bi-polar disorder. Many addicts are unusually sensitive in their feelings and prone to intense emotional reactions. Their emotional self-regulating centers are seriously out of whack.

Many would benefit from being on the proper medication–sleeping medication and/or psychiatric medication. Unfortunately some treatment centers won’t prescribe medication until a person has been clean and sober for six months. But if your child is using drugs or alcohol as a way to self-medicate—to numb intolerable feelings or level out intense mood swings—they aren’t going to be able to stay clean and sober without the help of psychiatric medication. Only when a treatment center was willing to give Pam the necessary medication at the start of her effort to get and stay clean could she stay clean long enough to get a solid footing in sobriety.

Not everyone needs medication, but you need to find out what might work for your child. There are also vitamin regimens (in lieu of psychiatric medications) that can restore the neuro-chemical brain imbalances from which addicts suffer. Do the research.

Spiritually, most addicts are in search of something larger than themselves. Drugs initially promise a glimpse into that larger reality, as well as offering relief from emotional pain. The drugs then become their Higher Power. Only when the addict realizes that they are pursuing a false god, which has now enslaved them, with disastrous consequences, can they turn for help to get clean. The only thing that can compete with the drug “high” is true sustained contact with a Higher Power. Take their spiritual aspirations seriously. If you can, help direct them to more productive avenues for spiritual experience.

5. I educated myself about drugs:

We live in a culture that condemns all illegal drug use, but in which the pharmacy shelves are filled with mind-altering chemicals prescribed by doctors and where TV commercials push pills at an alarming rate. And, of course, alcohol is relentlessly pushed in every media.

What is illegal and what isn’t is pretty arbitrary, as the failure of the movement to prohibit alcohol demonstrated. The movement in some places now to legalize marijuana also illustrates that specific drugs can go in and out of fashion and hence in and out of legal status. Marijuana, like alcohol, is potentially addictive, though it also, like alcohol, has potential medical benefits. Marijuana seems to have fewer long-term health risks than alcohol, and its use does not seem to be associated with violence the way the use of alcohol is. Why is alcohol legal and marijuana not? The answers are political and social, not based in a true assessment of the danger to users.

However, the fact is that marijuana is illegal in most states, and this fact has big consequences for its users. Once a young person has joined an “outlaw” activity, there is less constraint in moving on to other outlawed activities, such as harder drugs.

However, if you join the cultural hysteria about illegal drugs–the kind of hysteria that classities marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance, meaning that it is dangerous and has no medical value–your child will not take you seriously. He knows better. Middle school children know more about drugs than most U.S.congressmen. So you better catch up with what your child already knows. Start educating yourself by reading Dr. Andrew Weil’s From Chocolate to Morphine.

If you read Dr. Weil’s earlier book Natural Mind, you will begin to understand that we are never going to get away from mind-altering substances altogether, because the desire for altered states of consciousness seems to be built into the human being. The Christian church uses the sacrament of wine to help the believer to access the presence of Christ. Unless someone has access to spiritual reality through other methods, this universal attraction to mind-altering drugs will remain.

Drug abuse is not always from illegal street drugs. The abuse of prescription medicines is on the rise among young people. If your child has a true need for pain medications, make sure you monitor their use if you think there is the potential for abuse. Kids are also using inhalators, and a variety of legal stimulants. Find out what you can about the legal but dangerous drugs that might be abused by young people in your part of the country.

Sometimes mood-altering drugs are taken by those who really should be on psychiatric medication, or those who need sleep medication, but instead are self-medicating in a dangerous way. Investigate if your child needs to be on psychiatric medication or alternatively, if he is abusing meds he’s already on.

The heavy-duty illegal street drugs are primarily cocaine (and crack), heroin, and crystal meth amphetamine (speed). But many kinds of drugs are also in use on the street—from Ketamine (an animal tranquilizer) to Ecstasy (MDMA) to LSD, GHB, to many new designer variants of these chemicals. Their street use is solely for recreation or numbing of psychological pain and avoidance of meeting the challenges of growing up.

An important distinction to learn is the difference between street drugs used for recreation and psycho-active substances used for serious exploration of spiritual healing and awakening.

At this time in our human history every possible psycho-active medicine from every part of the world is available to anybody in the U.S. So there are young people in the U.S.today who are serious about using natural psycho-active substances which have been used as medicines and as religious sacraments by native cultures throughout the world for thousands of years. The three following “sacred medicines” are used ceremonially in native cultures. It seems that they cannot be used recreationally and are not addictive: ayahuasca (a South American tea made from two jungle plants used by native people in the Amazon basin), peyote (a desert cactus used by the Native American church and Indian tribes in Mexico), and iboga or ibogaine which is derived from a psycho-active root used by the African Bwiti people of Gabon in their initiation rituals. From what I understand psilocybin mushrooms (the “magic mushrooms” of Mexican shamans and elsewhere) are another true sacred plant, and can be used for a serious purpose if consumed in shamanic ceremony, but they can also be misused if used casually and recreationally. And, although the major “sacred plants” are not addictive, that does not mean they cannot sometimes produce very seriously disturbing results, including experiences of underlying psychosis.

There are modern chemical psychedelics which also, in the right setting and with the right intention, can have therapeutic and spiritual uses, such as LSD, DMT, and MDMA. These same drugs, however, can be misused as recreational drugs and their casual use can lead to much worse hard drug use.

Unfortunately, the U.S.legal system does not provide for any subtlety in classification for all these substances (natural and chemical). Like marijuana, they are all considered dangerous and of no medical value, just like heroin, cocaine, and meth-amphetamine. There is now, for the first time since the 1960s, some serious research going on into therapeutic uses of both the natural psycho-active substances used by native cultures (peyote, ayahuasca, ibogaine, and psilocybin mushrooms) and modern chemical psychedelics (MDMA, L:SD, and DMT). For more information on research approved by the FDA, see www.maps.org. Another resource for current research and almost anything else you might want to know about drugs is www.erowid.org.

Find out what, exactly, is the nature of your child’s involvement with drugs. It’s not likely, but possible, that they have a serious interest in using “sacred plants” in connection with ancient shamanic techniques for accessing spiritual reality. Native adolescent initiation ceremonies often involve the use of a mind-altering substances, so there is a many thousand year history of tribal young people using substances for the purpose of testing their courage and finding out who they are. This use is very different from a recreational interest in “getting high,” or using drugs to avoid growing up, or self-medicating a serious underlying psychological disturbance.

Again, if possible, you need to find out what they are using, and for what purposes.

***********

In the interest of candor, let me say what anyone who has read our book Love Unbroken, already knows. My daughter Pamela was greatly helped by the serious ceremonial use of ayahuasca in the context of a fully legal church in Brazil which regards it as a religious sacrament. She was also helped by taking ibogaine in the context of a U.S. government-sponsored research project. Ibogaine has the remarkable quality of breaking the craving for narcotics (heroin, etc.) for a period of time, long enough for the addict to begin serious treatment.

We came to regard these two native medicines as part of the solution to, not part of the problem of, our daughter’s extreme drug addiction.

Our book illustrates the healing effects of these substances and shows how they were crucial to our healing. But the use of these substances was certainly not sufficient for our recovery. They did not cure her disease of addiction. Both Pamela and I also needed the support of the more conventional paths for recovery—including Twelve Step work and psychological work.

Pam’s and my use of ayahuasca and her use of ibogaine puts our story of recovery very much outside the mainstream of addiction treatment. The conventional view is that addicts must be completely abstinent of all psycho-active substances in order to stay clean. Abstinence is the most accepted path for addicts for their recovery, and the only one sanctioned by NA and most treatment centers. It is also the only treatment path readily available in this country.

However, conventional treatment alone is not what worked for our daughter. I’m not advocating for these substances (working effectively with “sacred plants” requires a safe context and expert guidance, neither of which is readily available in theU.S.), but I do believe it’s important that parents learn of their existence.

It’s not necessary that you agree with me about the potential benefits of some psycho-active substances. You still need to learn the distinction between the many different types of mind altering drugs. Some are legal; others are illegal. Some in both categories are potentially helpful; some are decidedly harmful; and sometimes it depends on the context and intention of the user. Some of these are now being researched for their possible beneficial uses; some are protected by law in the U.S. as sacraments when used by recognized religions. Your learning about all these differences will help you to talk intelligently with your child about drugs.

You also do not need to agree with what I am saying here in order to benefit from the following additional steps I’m recommending.

6. I looked at my own co-dependency; I did my own inner work:

Addiction is a family disease and usually at least one parent has some level of co-dependency with the addict. Generally that means we are overly affected by the addict and determined to save him from his disease. There are many good books on co-dependency, which Al-Anon folks will tell you about.

I began to look at my own contribution to my daughter’s disease when I started going to Al-Anon. I recommend that you work with an Al-Anon sponsor (one-to-one work with an experienced member of the fellowship) and, if you work with a therapist, make sure it’s someone who knows the disease of addiction. A therapist who doesn’t understand addiction can do more harm than good.

Find some form of meditation practice where you can learn to calmly observe the contents of your own mind and feelings.

As you learn to observe your thinking processes carefully, ask yourself: “What am I telling myself about the addict? Am I assuming he can’t help himself and needs me to take care of him? Am I making excuses for him?” Most addicts have psychological issues underlying their addiction; they may also have learning disabilities or developmental delays. It’s important to be realistic about what level of challenge is appropriate for your child, but then make sure they do what they can do to be responsible for their own decisions and their own recovery.

As you observe your mind and feelings, ask also: “What am I telling myself about myself?” If guilt and regret dominate your mental and emotional life, learn how to forgive yourself. Whatever you may have done in the past, it’s over now. Whatever mistakes you made are forgivable. Remember you did not cause your loved one’s disease.

Observe your obsessive thinking about the addict. Are you addicted to thinking you need to save him? Are you addicted to the hero role? Do you secretly believe that your worry is necessary for his survival? Remind yourself that worry serves no purpose, it only makes you more tense and less likely to respond with equanimity to the next real challenge. But…it’s very hard to let worry go. Forgive the worrier!

You’re not alone in worrying. One beautiful spring day I became so absorbed in watching the oak tree outside my bedroom window reaching its tiny bright green leaf-hands toward me that for a full half hour I had no thought of my daughter. With a shock I realized that I had not been worrying about her at all, and then I worried that, without my worrying, she wouldn’t be safe! That was an eye-opener!

Remember that your mind’s conclusion that what is happening to your child is a terrible tragedy may not even be correct. Many addicts in recovery end up being grateful for their disease as it opened them to a new life based on surrender to a Higher Power. Addicts are often very courageous in exploring beyond the boundaries of ordinary consciousness. Such exploration would frighten the rest of us. You might consider your addict as an adventurer on a quest for his own identity, on a search for a higher power. We can never tell what role the addiction may be serving in the larger design of their lives. Letting go of what we assume we know opens up a spacious presence, rather than staying constricted in our small worry thoughts.

7. I stopped taking my daughter’s behavior personally; I detached with love:

The addict is in the grips of a powerful compulsion to use drugs. She is not doing what she is doing to hurt you. The addiction has a life of its own, and to one degree or another, the addict is possessed by her disease. Her negative behavior is not directed at you. You are not the target. When your child blames you or is defiant toward you, that is simply the disease talking.

Learn to distinguish between the voice of the addict persona and the true voice of your child, the one you remember from before the addiction took over her life. When the addiction is talking, don’t take any of it personally. The addiction is not accessible to reason or to love. It wants only one thing: more substances, more numbing, more escape, less reality, less responsibility, and ultimately the destruction and death of your child’s soul and body.

It’s a fine study to discern when the addict is talking and when the real self of your child is talking. And likely you’ll make the same mistakes I did: sometimes I believed her lies, and sometimes I disbelieved the truth she was struggling to tell me. This gave me yet another opportunity to forgive myself!

8. I let go of unnecessary care-taking:

If you find yourself doing for your child what he could be doing for himself, find a way to disengage. You will need to learn about “tough love.” It’s not the whole story, but sometimes it’s the way to go. It’s tough for parents to let go of the caretaker role. After all, it IS the role of the parent to take care of their young children, to support and protect them. So we have to un-learn some of the most basic instincts we have when dealing with the “cunning and powerful” disease of addiction when it shows up in our adolescent or adult children.

One good way to think about letting go of the caretaker role is to remember: you stay loyal to and caring for the real person inside your child, even as you confront, set limits, don’t rescue, and stop caretaking the addict persona your child has adopted (the Mr. Hyde monster). Caring for the real person inside means that you offer love, support, and faith in their capacity to get clean, and you back off when they are still in active addiction so that you don’t support their addictive behavior.

You’ll make your own decisions about your addict. But consider the following actions which we took:

- When Pam was in active addiction and wasn’t ready to stop, we did not let her live in our house nor did we give her any money or financial support (after she turned eighteen). To give money to an addict who is still using drugs, and ask her to use it only for good purposes—like rent or food—is like putting candy in the hands of a two-year old and telling her not to eat the candy but instead go to the table and eat her spinach. She can’t resist the candy, nor can an addict with money in her hands resist using the money to buy drugs. We cannot expect the addict to resist immediate gratification with drugs if we ourselves indulge them by giving them what they want rather than what is ultimately good for them (and for us in the long run).

- We got out of the way and let the disease of addiction run its course. When the addict has to experience the full brunt of the consequences of her own behavior—bad school grades, bad credit, lost relationships, lost jobs, sometimes even jail or homelessness—these

consequences have the best chance of waking her up to the reality of her disease of addiction. If we “save” her from the consequences of her drug use, then we also “save” her from the possibility of learning from her behavior. - We came to believe that the pain of using drugs had to become worse than the pain she would have to face if she stopped using them. It is very painful to get clean and sober. There’s the pain of real guilt to be faced. There’s the pain of the underlying emotional suffering which she hoped to avoid by using drugs in the first place. It’s painful to get clean and see the damage you’ve done to yourself and your loved ones. In order to be willing to endure this pain, Pam had to reach the point where the pain of using was worse than the pain of not using. When the painful natural consequences of drug use are “cushioned” for the addict by the family, she does not have to suffer the full weight of what she is doing to herself. This makes it less likely that she will “hit bottom” and be willing to do ANYTHING to get clean. Of course, Pamela might have died before she “hit bottom,” but at least she had a chance of turning her life around because we weren’t cushioning the painful reality of her life as an active addict.

- Shocking as it may sound, we did not intervene when she went to the streets and became homeless. In our case we didn’t really have a choice because she went there on her own. But as long as she was on the streets we didn’t send money for food or help her find a place to stay. We didn’t bail her out of jail and we didn’t pay medical bills. And she knew we wouldn’t.

- On the other hand, we kept contact open with her. We accepted collect calls and even got a toll-free number. In every call we reassured her that we loved her, and always would. We researched various treatment options and, if she was open to hearing, we presented them to her. We were willing to transport her to treatment and pay for treatment, as we were able.

- I kept a list of DO’s and DON’Ts by the phone where she called.

DON’T DO

Panic. Instead, stay calm, no matter what

Push help at her. Instead, let her know help is available

Nag or lecture. Instead, respect her unique path

Accept abuse. Instead, let her know your limits

Tell her what to do. Instead, hear what she is doing for herself

Try to control. Instead, surrender to what is

I also kept by the phone a New Yorker cartoon of a Mom rushing into her skinny teenager’s room where he was diligently lifting weights. She exclaims, “Here, let me help you.” Yep that’s me. Reminding myself of my tendency to over-help allowed me to back off a little more.

9. I learned to take care of myself:

Remember to take care of yourself. Get a massage. Take a long walk. Go to a good movie. And do your spiritual practices. Daily walks and daily prayers and meditation were all that kept me sane during several particularly stressful periods of Pam’s active addiction.

If you are in a primary relationship, pay attention to your partner. An addicted child can ruin a marriage, as one partner tends to be the enabler (that was me) and the other tends to be the tough guy (that was my husband). We fought over the best way to parent Pamela, with my husband criticizing my style as too permissive and me criticizing his style as too unloving. As parents take opposing roles, they can become estranged. Take time to enjoy each other. Remember your love. Respect your differing parenting styles. Get into couples counseling, go to Families Anonymous meetings together, have fun together.

10. I let go of control. I surrendered to a Higher Power:

You can’t possibly go the distance with your child unless you also cultivate a spiritual approach to life and find comfort in surrendering to a Higher Power. How you do this is strictly up to you: whether you find a spiritual connection through deeper practice of your own religious faith, or through your Twelve-Step work, or through any other spiritual path and practice. However you do it, I strongly recommend that you give first priority to your spiritual life.

And if you don’t yet have a relationship with a Higher Power, you now have in your life exactly the perfect life circumstances that sooner or later will break your heart open and bring you to your knees in prayer. So let yourself be cracked open by this disease; it will bring you to your own deeper understanding of God.

By God I only mean that unnamable but trustworthy essential energy of life—that intelligent, loving presence—that can be touched in our own deepest being and which we can come to know as the only power truly behind this whole human drama. And we can learn to surrender our little will (our illusory sense of control) to the will of this greater power.

We specifically need to learn to trust that this Higher Power is operating in the life of our addict. Something is in charge of his life, and it isn’t us. We can love him, but we aren’t in charge and the sooner we learn that, the saner we will be.

If you are like me, the first three steps of the Twelve Steps will need to be worked with over and over: Step 1: Admitted we were powerless over the disease from which our child suffers, Step 2: Came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity, and Step 3: Made a decision to turn our lives and our will over to that Higher Power. Sometimes I needed to repeat those three steps over and over as a daily mantra. The Serenity Prayer is another good daily mantra: God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

What may surprise you most of all is that this terrible family affliction of addiction may actually serve to open you up to personal growth and spiritual awakening as it did in our case.

11. I created and maintained a loving alliance with my daughter:

With all I’ve said about maintaining boundaries with the addict (“tough love”), it may come as a surprise that I still think the single most important thing you can do is create and then maintain a strong loving bond with your addicted child. If you had a strong bond in the first place, trust it and remember it (even if you can hardly now recognize the child he once was).

If your child was a non-infant adoption s/he is apt to have what is called an attachment disorder—that is, the child never fully bonded in love and trust to a primary caregiver. Get the counseling of someone trained in attachment therapy to help you understand the issues your child faces, and take a good look at your own difficulties in bonding because you’re half of what’s needed for him to sustain a loving bond.

And remember it’s never too late for that bond to be established. Pam had a serious lack of attachment to me or anyone when she started her downward spiral with drugs. Through my many efforts to reach out to her (including several failed rescue missions), Pamela finally came to trust my love for her. She tested my love over and over, until she finally believed that I would never abandon or reject her, that I would always keep the light of hope for her recovery alive in my heart. She finally knew, to the depths of her being, that I loved her unconditionally.

Unconditional love doesn’t make us wimps. It was the combination of affirming the bond I had with her (the unconditional love part) AND confronting the behavior related to her addiction (the tough love part) that was the potent combination that allowed me to become a positive healing presence in her life. A mushy love that allowed her to abuse me would have killed our relationship and just added a destructive guilt on top of the burden of addiction she was already carrying. But a tough love that cut her off from me would also have killed the principal lifeline she had.

It’s not always clear what is enabling and what is caring, or, on the other side, what is appropriate detachment and what is cutting off. You will probably make mistakes at both ends of the spectrum, as I did. I gave her a place to live when she was just wanting respite, not recovery—that was enabling. On the other hand, a few times I cut off contact because I believed some expert who told me that was the way to treat an addict, and later I regretted it because I realized that this behavior only added to her terrible feelings of isolation and unworthiness. So I know that it’s not easy to find the proper balance.

Eventually, however, I did learn how to both hold a firm line around her addictive behavior AND to keep my heart open to her, even when she was behaving very badly. This meant, of course, that my heart broke many times over in my loving of Pamela.

Addiction is a heart-breaking disease. To keep your heart open to your addicted child is the biggest challenge you will have. But to cultivate unconditional love in any relationship, you must be willing to let your heart break. Over and over. Don’t be afraid of emotional pain; it won’t kill you. It can actually be good for you. It will help you get humble and real, it will open up your need for help, and it will challenge what may have been your fixed ideas about your “good guy” persona. Loving an addict will change you … for the better.

If you go all the way with your breaking heart, you will discover something very magical: your heart will just keep getting bigger and bigger and stronger and stronger. A contemporary spiritual teacher has written:

“Opening to whatever is present can be a heartbreaking business. But let the heart break, for your breaking heart only reveals a core of love unbroken.”[1]

If you want to know how I did it … well, you’ll have to read the book because that’s what it’s about.

12. I was there when she was ready for treatment:

I always gave Pam the benefit of the doubt when she said she wanted to get clean and was ready for treatment. We usually believed her and we supported her to get whatever form of treatment she was ready for (and we were willing to pay for) at the time. She went to several treatment programs that did not “work,” in the sense that she never successfully finished the program. However, even a short time spent in these programs helped her understand the nature of her disease and gave her a glimpse into what recovery was really all about. I don’t regret funding any of her many attempts to get clean; they all added up to a final readiness.

I also did a lot of research for Pam about her options. It was my assessment that finding a program was beyond her capability, and so this felt like help I could offer. In the end the only treatment program that “worked” for Pam—that is, the one which lay the foundation for her life now as a clean and sober adult—was a program that began with her taking ibogaine (in the context of a government-sponsored research program for addicts), and that honored the spiritual growth she had made as a result of her years of drinking ayahuasca. She still relapsed even after a year in this program. But her final relapses were short and temporary.

One thing needs to be clear: Nothing you do or don’t do will guarantee that your addict will make it. We cannot take credit for their recovery any more than we are to blame for their disease. It is all part of the great mystery of life. I consider Pamela’s recovery one of the great miracles of my life. Such miracles come to us sometimes, through the grace of God. When we do the work of our own recovery—so that we can be there for our children—miracles are just a little more likely.

I offer this “Advice” with the utmost respect for whatever way you meet this challenge in your life, with utmost tenderness for the struggle you’re going through, and with great faith in the parental heart we share.

God bless you,

Susan Thesenga

[1] Gangaji,

contemporary American teacher, from A Diamond in Your Pocket. The title of my book Love Unbroken is taken from this quote.