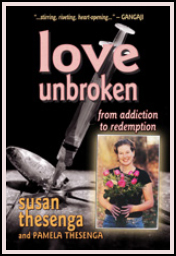

I am posting again something I wrote over 10 years ago, a week after my mother died. This essay appears in a book recently released, entitled Saying Goodbye to our Mothers for the Last Time.

A Good Death

Susan Thesenga, May 2005

My mother died last week. I had the great privilege of being with her at the time of her death, and for most of the two weeks before she died, as well as caring for and sitting with her body for the two days following. The services of Hospice let us care for her at home until her death, and we were also helped (by another service) to care for her body after her death. Her body lay quietly in her own bed until we placed it in a casket, which we then accompanied to her burial.

Being with my mother in her dying and with her body afterwards was intimate, profound, and deeply reassuring. I was given glimpses of the perfection of God’s great design, as every detail of her passing seemed so perfect. And I felt the completion of a karmic cycle, knowing I had fully worked through my issues with her. At her death we entered into a deep union.

I was able to give my mother in her dying what she had not been able to give me in my birthing—physical intimacy, visceral reassurance, emotional warmth, and a feeling in the room of safety, fearlessness, and peace. In offering this deep connection as one of us transitioned from embodied awareness to non-embodied awareness, it hardly mattered who was mother and who was daughter, or whether the passage was into or out of the body. The transition at death out of the body and into the Mystery is no less wonderful than the transition into the body at birth.

The Hospice chaplain used exactly this metaphor with my mother, inviting her to consider that, just as humans on “this side” welcome a soul into a new body, she might be welcomed also on the other side to a new state of consciousness, traveling through the “tunnel” of death, paralleling the journey through the birth canal. My mother, who was not religious, though always open and curious about life, liked the metaphor. And so I used it often in my attempts to reassure her and guide her in her passage.

Just outside the window of my mother’s bedroom, in which she lay dying in the hospital bed Hospice had arranged for her, a mother duck sat on eleven eggs in a nest on the patio. Birth and death were that close. Two hours after my mother died, Michelle, the Hospice nurse who had beautifully guided us through every step of the dying process, came to visit, even though her job was done, and even though it was her birthday that day, saying that when she woke up with a dream of baby ducks, she knew my mother had passed.

I had incredible support and help with my mother–not only from the Hospice staff, all of whom were terrific, but also from my sister Martha, who came regularly and was supportive, and from Maureen, who had become my mother’s full-time caretaker. I could not have done this without everyone’s help.

After my mother’s passing, we had the service of a woman, Beth Knox, who helped us to take care of the body, dressing her and laying her out in her own bed, radiating the peace that I suspect comes from a good passing, and subsequent loving care. Beth, whose services I would highly recommend, runs an organization (ww.crossings.net) for those who wish to care for their own dead. Beth came to this work through her own personal tragedy of losing a young daughter to an airbag accident. She was with her daughter in the hospital at her death, and fought the hospital’s policy to send dead bodies to funeral homes. She convinced them of her right to care for her own daughter’s body, and took her home.

It is perfectly legal for anyone to do this. Most of the myths and fears we have about death, and dead bodies, are fostered by the funeral industry. There was no smell, no decay, and no health hazard whatsoever in having my mother’s body cared for at home, which, of course, is what families always used to do. It was also essential that we had Beth’s help in caring for the body, because she knew exactly what we needed to do at each step. And she works with a funeral home that is sympathetic and will provide only those services the family wants. (We had a casket delivered to the house, into which we transferred my mother’s body, and we had them provide a hearse and limo to the cemetery. And that was all. Most funeral homes try to sell you on the false idea that embalming is necessary, and that they have to do everything. It isn’t and they don’t. Embalming only came into practice during the Civil War when bodies had to be shipped long distances after being dead a long time; it is not necessary and is horribly invasive to the body.)

Having the body at home was a great lesson for the grandchildren. My daughter Pamela was at first scared to see her grandmother’s body, but when she eventually chose to go into the bedroom, she fell into a state of reverence and amazement, commenting on how beautiful her grandmother’s body looked, how peaceful and radiant her face was, and how evident it was that she, the grandma Pam loved, was no longer there. Pamela described going through a “wall” of fear of death, and said she now felt much more comfortable and grounded. Now she just wanted to know where grandma had gone, which gave us an opening for some important spiritual sharing together as a family.

My mother’s great dignity and deep kindness were evident in her dying process, and both were reflected in her face at her death. As long as she could still talk, she always thanked us for everything we did for her. She graciously received the hymn singing and prayers that were offered to her by friends from my church. She spent time with everyone she loved in the two weeks before she died, waiting until the last grandchild who was finishing college exams could come. Then she waited one more day to die until I was with her, as she knew how much I wanted this. Knowing her time was near, Maureen and I both slept in the room with her. During Mom’s last night we all slept deeply and peacefully. When we awoke at 6:00 a.m. my mother was still breathing, but took her last breath minutes later with both Maureen and I present, and well-rested. Even in this detail her consideration for others shone through.

My mother was intelligent and liked to know what was going on. She grilled the nurses on exactly what physical changes would take place, even though she didn’t always like what she heard. She reported her observations of other realities as they began to appear—her awareness of a man in a dark suit coming for her (who looked, to her, like Elvis Presley!), her “dream” of a beautiful ballroom where many of her dead friends were dancing, and which was very peaceful. Even the changing “pictures” she saw on the wall were reported with a curious and detached interest.

My mother liked to be in charge. She kept control of her environment as long as was feasible. She wanted to know everything we were planning, and when I finally suggested that it was time to let go, because Martha and I had everything under control, and that we even agreed on everything, she quipped, with her usual quick wit, “Well, that’s worth dying for!”

My sister and I were blessed with a deep harmony during this time. We agreed on funeral and burial arrangements, casket, and all the other choices one needs to make. I felt entirely supported as she let me take the lead in the emotional and spiritual arenas where I am strong, and I gladly followed her lead in all matters financial and legal, where I have complete trust that she will execute matters impeccably.

I have waited much of my life to be present for a conscious death. My father died suddenly; my stepson died prematurely; my childhood best friend was already unconscious when I sat with her until she passed; my Pathwork spiritual teacher was in denial until almost the moment of her death; and my first church spiritual teacher died without warning. It is one of the great wonders of my life that my own mother became the vehicle through which I could experience dying consciously.

In the moments after her passing, as I sat on the bed, holding her hand, I wept, not so much in grief (that would come later) as in gratitude, because she had let me so fully be with her in this most profound of all the passages we must each traverse. I felt the merging of our consciousness, and was flooded with awareness of the deepest peace I have ever known. I felt that I was going with her to this place—of pure peaceful awareness, of empty fullness, of vibrant nothingness—that is the ground of our being, the place we “come from” and the place we return to, and the inner reality behind our outer lives. It was her final and greatest gift.

Thank you, Mom.

Susan Thesenga

Sevenoaks, Madison, Virginia

May 17, 2005